In 2014, when Muhammadu Buhari started campaigning, again, to become Nigeria’s president, he opened accounts on Twitter and Facebook to supposedly ‘engage the populace’ using tech communication tools, following comments from the then ruling Peoples’ Democratic Party (PDP), labelling him a “semi-literate jackboot”.

“Good afternoon my friends! This will now be my official Twitter handle to communicate with you. – GMB,” his first tweet read.

“I and my office will speak to you from here. Personal tweets will be signed GMB,” he said in another tweet.

At that time, people were tired of the Goodluck Jonathan administration, and the Chibok kidnap shook the country from its roots. You will recall that #BringBackOurGirls became a global hashtag.

Social media provided means to engage the ‘saviour’ that wanted to be president, and his campaign team – Buhari Campaign Organisation (BMO) – were not going to leave any stone unturned.

BMO continued to publish damning accusations against Jonathan, and Buhari’s minions (paid and unpaid), who brought ‘Sai Baba’ from the streets to social media, made sure those accusations went as far as social media algorithms could take them.

More people joined the campaign, and the message kept spreading from online engagements to offline activities and vice versa.

EVERY TIME I MEET AND INTERACT WITH YOUNG NIGERIANS FROM EVERY PART OF THE COUNTRY, I AM STRUCK BY YOUR VITALITY, CONFIDENCE, INTELLIGENCE, CREATIVITY AND VISION. THESE ARE THE INGREDIENTS NEEDED TO FORGE A GREAT COUNTRY. THE ONLY MISSING COMPONENT IS VISIONARY LEADERSHIP THAT WOULD CHANNEL YOUR ENERGIES AND RESOURCEFULNESS INTO COHESIVE SOCIAL AND ECONOMIC MECHANISMS TO DEVELOP NIGERIA.

Muhammadu Buhari, December 2014

BMO employed the best digital media campaign team, and we could see the effects. People began actively taking the gospel of change to their friends, family, and neighbours – the ones who do not use social media and the ones who refused to get the message.

Change is here, are you so unpatriotic to not support this change?

A good deal of the rebranding from Major General Muhammadu Buhari (rtd.) to ‘reformed democrat’ happened online, where campaigning from smartphones and laptops can build momentum with just one tweet or one post.

“The digital strategy has been a lifeline of the campaign for young people. We needed to create an image that enabled people to connect with him,” Adebola Williams of StateCraft, told Reuters before the election.

Goodluck Jonathan’s team also used social media against Buhari, including video clips on YouTube showing his time as a dictator. But with #OccupyNigeria (which started online) and the Chibok event (top ten most searched on Google trends), ‘change’ (the mantra of the newly created APC) was what everyone wanted.

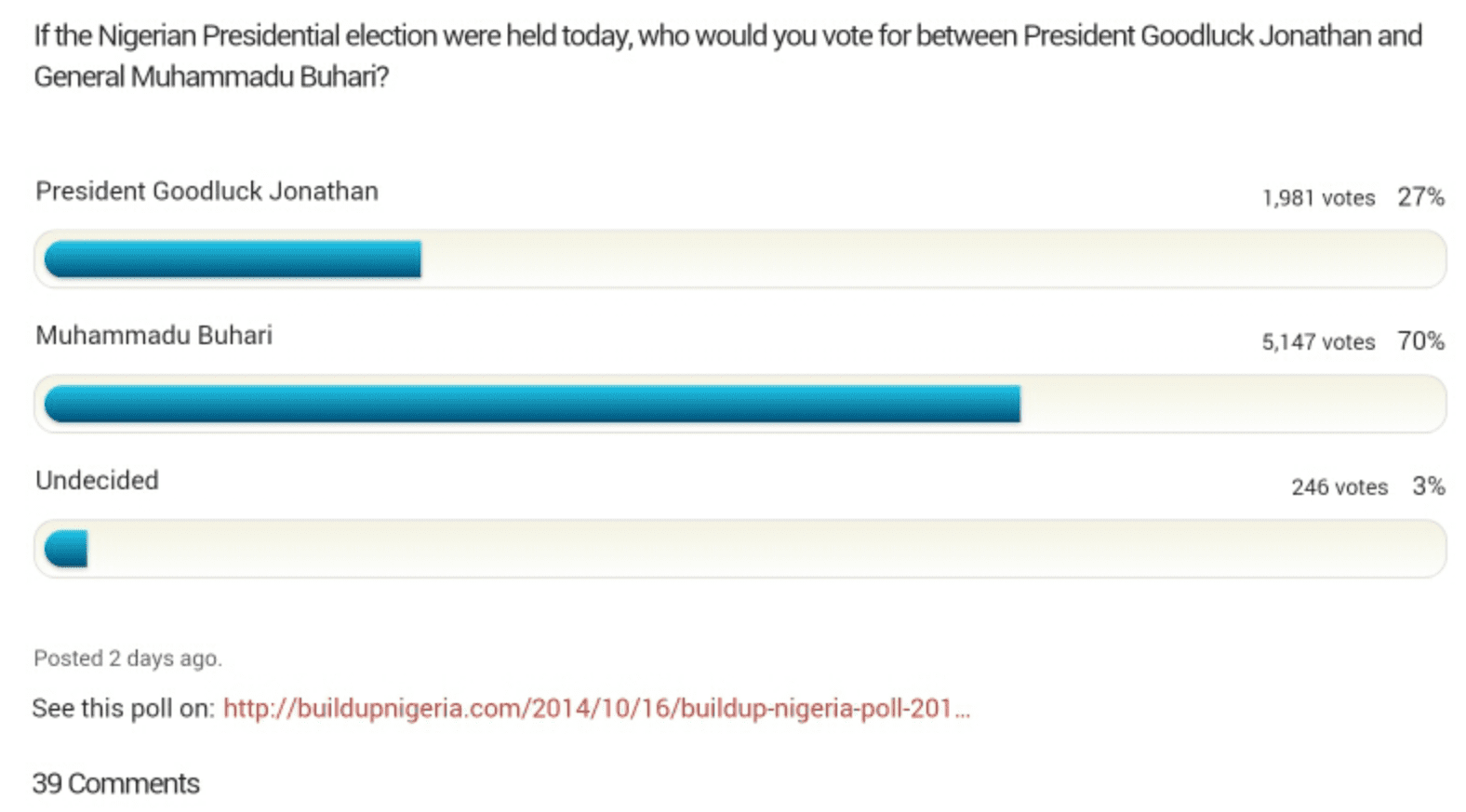

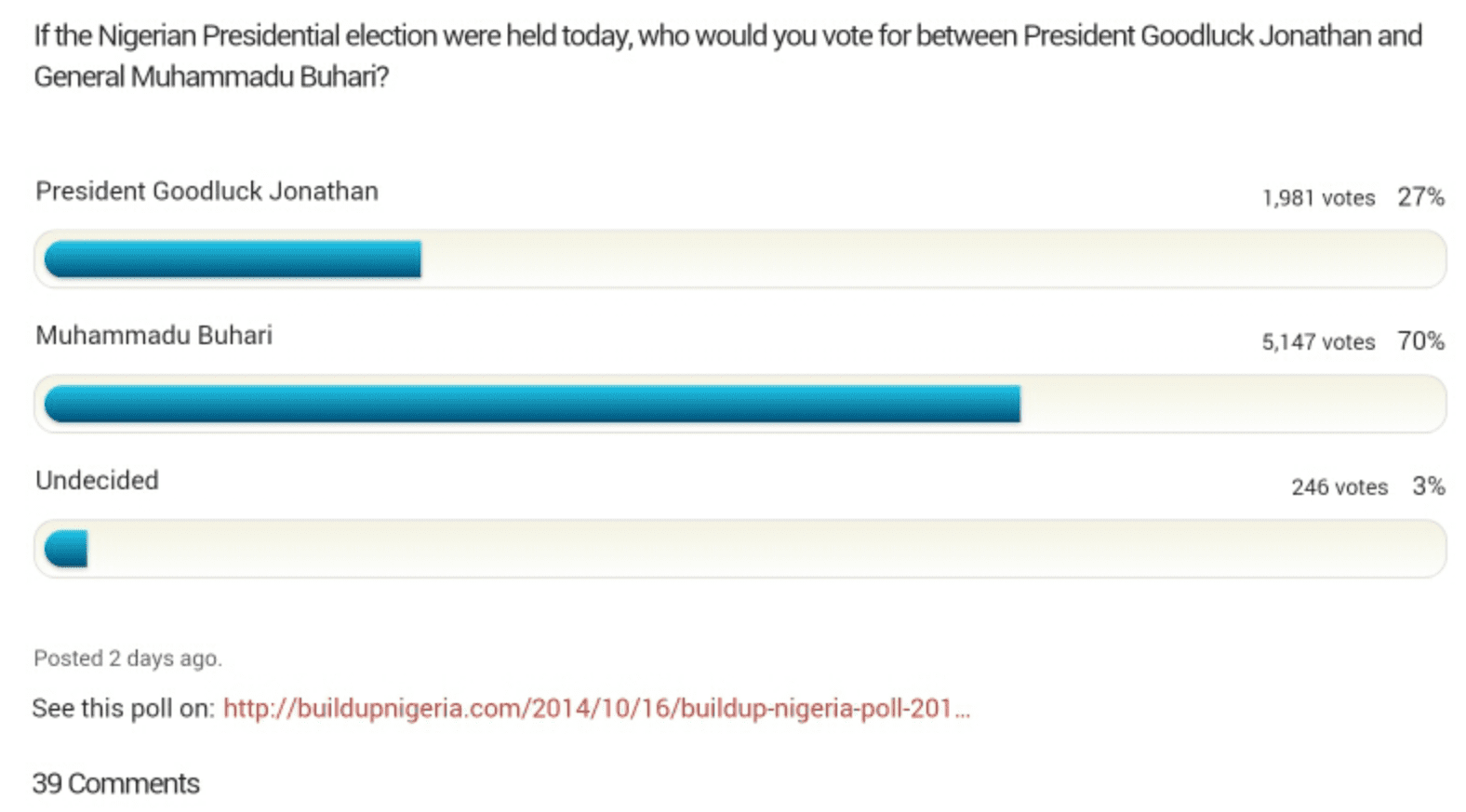

On October 15, the day Buhari declared his intention to run for president in the 2015 election, news website, Sahara Reporters, activated an opinion poll asking Nigerians to indicate who they would vote for if the election were to hold that day between Buhari and then President Goodluck Jonathan.

The poll lasted for only 24 hours, and out of a total of 15,435 persons that voted, Buhari got 12,246 votes, representing 79 per cent of the total votes cast, while President Jonathan got 3,189 votes, representing 21 per cent of the total votes.

There were others:

Buhari defeated a sitting president and social media had played a big role, not forgetting that Buhari won most of the polls that took place online.

Read also: Looking for better days: The real stories of Lagos dispatch riders

Buhari – as a search term on social media/Google

Muhammadu Buhari was the second most-searched person in 2015, according to Google trends as interest, a consequence of the online campaign grew wider. But when compared to Goodluck Jonathan in 2014, the latter comes first. This means that people were still interested in the topic – Goodluck Jonathan. Besides, he was still the president.

The comparison in 2015 stays the same, but this time, the gap reduced, indicating that people’s interest was switching amid a ‘change’ narrative that filled our social timelines in that period.

Because posts on Facebook are private, you will have to search for hashtags to know if people are talking about the search term.

You could see how many people were talking about #Buhari or #SaiBaba, but it is impossible to streamline that search period to 2014/15. So, as of writing this, #Buhari has 55,000 people talking about it, and #SaiBaba has 44,000.

But, neither of those search results is country or time specific.

For Twitter, you will see live trending topics, and 2014/15 had some of those related to Muhammadu Buhari, including #Change, #SaiBaba, #ReformedDemocrat, #Buhari, etc.

On YouTube, the trend kept going up and down, indicating that when a video about Buhari is posted, people rushed to see what it is about, but that interest waned almost immediately after.

“Change” was coming and supposed propaganda was not going to alter the narrative.

But, the saviour illusion that was created in 2014 was non-existent when Buhari declared his intention to run for a second term in 2018. The search was streamlined to most people in Northern Nigeria, and only the tenth on the list of search sources was Anambra.

The conversations on social media were split between #Atikulate (from Atiku Abubakar of the PDP), who had another supposed saviour, Peter Obi, as his running mate.

On Google trends, #Atikulate got increased interest at the tail end of 2018, but the conversations on social media were not as powerful – Atiku Abubakar was perceived to be in the same class as Buhari, knowing that he had helped Buhari emerge as the president in 2015.

Atiku lost the election and Buhari still won part of social media. But, he had pulled a campaign that shook Buhari’s camp.

PHOTO: BBC

Less than a week after the 2019 presidential election campaign was kick-started, an online poll took place and Atiku won.

Atiku scored 98% of the votes against Buhari’s 2%. An analysis of the total votes cast of 10,496 showed that former Atiku secured 10,286, and Buhari came a dismal second with 2,090 votes.

Online voters were asked “If elections are today, who would you vote?”, and was conducted by @buhari42019 (a now-suspended account).

The same fate befell Buhari as Atiku defeated the president in the two polls conducted simultaneously by Japheth Omojuwa.

In the first poll, Atiku had 35% of the votes compared to Buhari’s 32%. In the second poll, Atiku secured 39% of the votes while Buhari came second with 34%. It gave an inkling that #Atikulate was working.

A case study

Social media, with some 233 million users in the US and already a major communications platform, is believed to have taken on a heightened role of importance and ability to influence leading up to the election with people relying more on virtual communication during the COVID-19 pandemic. This may have both positive and negative consequences.

Hayleigh Moore & Mia Hinckle

In an article by Forbes, Social Media Could Determine The Outcome Of The (US) 2020 Election, social media was prioritised as an indispensable platform for reaching youth and causing an increase in engagement during the election cycle.

And, NPR, in an October 29, 2019, article on surging youth turnout, shared that the number of early voters under 30 who are voting for the first time in their life is more than double the number of first-time voters at this point in the 2016 election.

Social media’s influence on US elections was evident in the early 2000s. Barack Obama harnessed social media in his first presidential campaign to rally a majority of voters and win the 2008 election.

Around 74% of internet users sought election news online during Obama’s first campaign, representing 55% of the entire adult population at the time, according to Pew Research Center.

The Donald Trump campaign made extensive use of social media platforms, notably Twitter, to reach voters. Trump’s Twitter and Facebook posts linked to news media rather than the campaign site as part of his strategy to emphasise media appearance over volunteers and donations.

Based on the data gathered by the Pew Research Center, 78% of his retweets were from the general public, as opposed to news outlets and government officials.

Trump’s unique use of social media compared to other candidates garnered critical attention, as he harnessed Twitter as a platform to respond quickly to his opponents and tweet about his stance on various issues.

Later on, in 2020, a Facebook executive, Andrew Bosworth, claimed in an internal memo the company was “responsible” for Donald Trump being elected as US president.

Bosworth said Trump was not elected because of “misinformation”, but “because he ran the single best digital ad campaign I’ve ever seen from any advertiser. Period”.

Bosworth told staff that it was not foreign interference that helped Mr Trump get elected, but his well-planned campaign.

“So was Facebook responsible for Donald Trump getting elected?” questioned the long-time employee. “I think the answer is yes, but not for the reasons anyone thinks.”

But, like Goodluck Jonathan, he (Trump) could not win the social media game with Joe Biden. The similarities are US citizens had gotten tired of the Trump administration, and the Democrats also leveraged social media to spread the gospel of change.

The Peter Obi instance

You cannot doubt the buzz that is happening with the Labour Party 2023 presidential candidate, Peter Obi. You could almost scroll 10 minutes on Twitter before you are free from the situationship.

On Google Trends, the search term – Peter Obi – spiked in mid-May, but was rescinded in early July.

YouTube is experiencing a Peter Obi spike too.

On Facebook, about 19,000 people use the hashtag #PeterObi in their posts. Users are using videos, and photos, to tell the story – past projects of Peter Obi, pre and post-governorship era, and clips of interviews he has had since declaring his intention to run.

Others are using #PeterObi to discredit the current administration and the two major political parties, APC and the PDP.

Peter Obi, 60, had stayed with the PDP after his running time with Atiku, but he could not play the politics of the PDP this time and defected to the Labour Party before it was too late. There, he was made the party’s candidate. It is after this, influenced by the disillusionment of the two parties that Obi started electrifying young Nigerians.

Again, it is the need to uproot the current cycle of politicians that is influencing this. The country, as in 2014, is looking for a saviour who says he is ready to solve the country’s myriad problems. And, young social media-savvy supporters have elevated Peter Obi to a saviour status, and are fighting anyone who says no to the campaign.

His supporters have sparked conversations and have made sure these appear on the trends table, further widening the message.

‘Soro Soke’ would have been the best term for this massive group of strong-willed, independent-minded social media users who argue that anyone other than Obi will be an aberration.

On Instagram, the hashtag #peterobi has over 25,000 posts, which record all his activities as the country prepares for the general elections. And, we all know that eight months is enough time to spread the name to every corner of the digital space.

However, there are other candidates, whose lips (and their followers) are not shut, and whose keypads are not stiff.

The numbers and possibility of influence

…Since the turn of the new epoch, the internet and social networking sites like Facebook and Twitter have become new opportunities to energise political participation and civic engagement in democracy and modern politics.

(Milakovich, 2010)

Political actors and organisations are known to have used social media knowing that is it a fast and effective way to mobilise support and canvass for votes (Okoro & Nwafor, 2013; Madueke, Nwosu, Ogbonaya & Anumadu, 2017; Opeibi, 2019).

For instance, President Muhammadu Buhari created personal Twitter and Facebook accounts to promote his presidential ambition. He used the platforms to mobilise support, persuade, influence, and educate voters during the electioneering period, while former president, Goodluck Ebele Jonathan of the PDP, utilised cyberspace as a platform to report achievements and solicit further support (Tunde Opeibi, 2019).

It is the turn of either Bola Tinubu, Atiku Abubakar, or Peter Obi, but what can they do with the social media users on their side?

In 2021, it was claimed that Twitter Nigeria has 39.6 million users, but the claim was faulted by Dr Isiaka Olarewaju, a statistician, according to Africa Check. He was previously the head of household statistics at the National Bureau of Statistics (NBS).

No credible data supports the widespread claim that there are 40 million Twitter users in Nigeria, according to a report by Africa Check.

In a 2021 digital report, Hootsuite estimates that Nigeria has 33 million active social media users. Twitter is ranked as the country’s sixth most used platform, behind WhatsApp, Facebook, YouTube, Instagram and Facebook Messenger.

The report says a Twitter ad in Nigeria has a potential audience of 3.05 million people. But it adds that audience figures “may not represent unique individuals or match the active user base”.

So, it is possible that Nigeria has only a little over three million Twitter users.

As of March 2022, there were over 36 million Facebook users in Nigeria, accounting for 16.5 per cent of the population. Overall, 33.2 per cent of users were aged between 25 and 34 years, making this age group the largest user base in the country, followed by those aged 18 to 24 years. Just 4.5 per cent of users were aged between 13 to 17 years. Additionally, 5.5 per cent of users were aged 65 and over, according to Statista.

There were 8,676,000 Instagram users in Nigeria in January 2021, which accounted for 4% of its entire population.

The number increased in March 2022 to over ten million Instagram users. Overall, 38 per cent of users were aged between 25 to 34 years, and 30.2 per cent were aged between 18 to 24 years. Just 2.8 per cent of users belonged to the 55 to 64 year age category. Additionally, 42.3 per cent of users in the country were women, according to Statista.

In total, it means that there are about 50 million social accounts – excluding LinkedIn, WhatsApp, and TikTok, though only 15-20 million of that number may be the actual number of users.

These platforms are becoming a dominant factor in electoral processes, playing a tremendous role in the creation, dissemination and consumption of political content.

The Conversation

In a March 30 article, Algorithms, bots and elections in Africa: how social media influences political choices, The Conversation writes that “imbued in social media platforms, with the exception of WhatsApp, is a system of software, codes and algorithms that manage, interpret and disseminate large quantities of information across social media networks.”

“They have the power to amplify and marginalise certain content and, like human gatekeepers in traditional mass media, determine what information users are exposed to,” it continues.

It goes on to say that social bots can help manipulate public opinion and influence votes. And adds, “It is evident that those with political power and money can easily hire automated systems, like bots, to influence the flow of political content across social media. They can also distort information. The role of non-human actors should be worrying to anyone keen on democratic processes.”

The role of social media in today’s elections cannot be overemphasised.

If five million young Nigerians across Nigeria decide on one person for a presidential election, and two million of those actively spread that message beyond the shores of social media, there is a possibility that 15% of the number of eligible voters (84 million as of 2019) will be swayed towards that candidate.

And, seeing reports of the number of young Nigerians willing to participate in the 2023 elections, 84 million may turn to 100 million or more. Do the maths.

However, poverty has always been a weapon against the masses, and while everyone wants a better country, there are those who just want that NGN1,000 and the souvenir to survive that day and the next. “The future” is not on their calendar at that moment.