In the late 15th and early 16th centuries, after the death of Oba Ozolua, the king of Benin, war ensued between two of his eldest sons, Esigie and Arhuaran about who should be the next king. With the help of his mother, Queen Idia, Esigie was successful in the war and took over Benin and its territories.

In gratitude, he names Queen Idia, Iyoba, the first of its kind, a title that makes her wield as much political power as a senior chief. In reverent to her legacy, the king commissioned a mask, made of ivory to be created of her face.

Centuries later, in what historians now regard as the Benin Punitive Expedition of 1897, British military officials invaded the Oba of Benin palace and looted the Benin artefacts including the Queen Idia mask. After another century, those artefacts, known collectively as the Benin Bronzes, are held in museums in London, Stuttgart and New York.

In more recent times, contentions over the Benin Bronzes and who should be their guardian have engulfed the art world, from Berlin to Lagos.

The Benin Bronze NFT Exchange Project

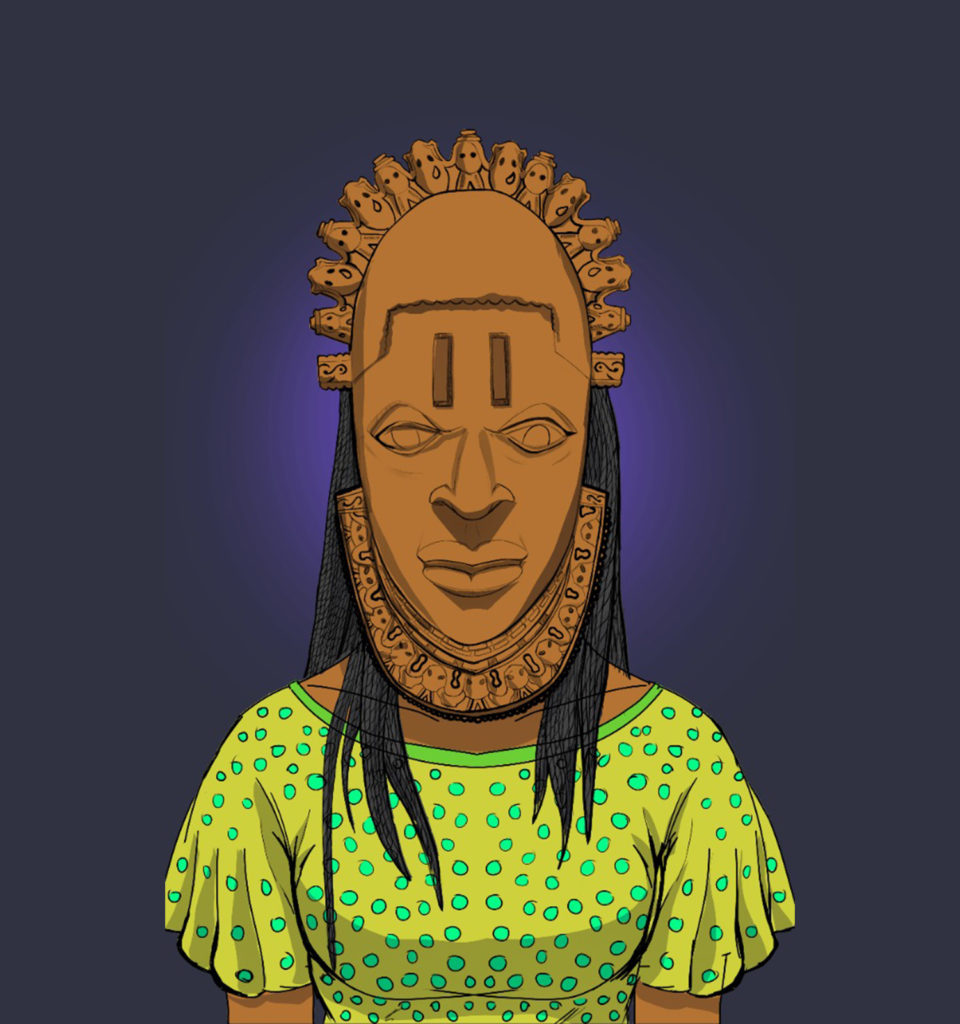

With the emergence of NFTs in Africa, a path to some version of the Benin Bronze will greet Nigeria (and other parts of the world) next month. A new collection of 1,897 NFTs inspired by the Queen Idia mask has been designed by the Benin Bronze NFT Exchange Project using blockchains and web3. It will be released on the 8th of February and will be available for sale to anyone who can buy it all over the world.

Tunde Anjorin, the editor in chief of Panaramic Comics, who spearheads the project and his team are focusing on the Queen Idia mask with the collection.

His curiosity about the mask pushed him to embark on the project. He wants people to know about this mask of this political strategist who was a woman in 16th century Nigeria that was looted and now seats at the Metropolitan Museum in New York.

“It’s a curiosity kill the cat strategy where you see outfits in cultural attires and jewellery that resonate with you, then you’re asking yourself ‘what mask is that?’” he said in an interview with Technext. “We want people to know about these masks taken from Nigeria.”

In a research carried out with his team, despite the Benin mask being featured in The Black Panther movie, Anjorin said that he was surprised to find that the Benin masks are not as popular as one would have thought.

“We looked for the top 10 most recognisable masks in the world and we saw that the Benin Queen Idia mask did not come up,” he said.

As stated on their website, the objective is to “use a range of cultural attires with a focus on one of the 3 Benin Ivory masks, fostering social connection in order to drive awareness about the Benin Bronzes being away from its creators, creating value for its NFT holders.”

“Our goal is to let the global community on the internet know that these masks are creating value for people who are not the creators,” Anjorin said. “We want to create awareness and spearhead conversations about the Benin Bronze.”

Why NFTs?

“Why not NFTs?” Anjorin asked. “We are clearly moving into an era that is termed ‘web 3’…attaching your finances to your online presence. The world is moving in that direction. It makes sense to see what things would be like from an African perspective…Things that were lost can be recreated.”

He went on: “If we can use technology to create a replica of the Benin Kingdom so that people can see what it was like, why not do that? It means a lot in re-educating the world with regards to the mighty ancient empire of Benin, and remind people in Edo State Nigeria what greatness they’re surrounded with.”

At the core of the debate is that modern Benin City doesn’t have the facilities and can’t keep up with the logistics to maintain the Benin Bronzes that are worth millions of pounds. Advocates for the return of the artefact disagree, arguing that they should be returned to their origins. With these NFTs, a wide range of the Benin mask will be spread across the world.

“People go to these museums in the West and they pay for tours to learn about these things but these masks were not created there. Our aim is to accelerate knowledge about the Benin mask, the Queen Idia mask,” Anjorin said.

How did Anjorin go from editing comic books to making NFTs inspired by the Benin masks?

“I heard of NFT a lot towards the end of 2019 and I naturally was just trying to understand with every person ‘what exactly is an NFT?’” he said.

“We were in a post lockdown world and as things slowed down people had to restrategize and adapt to the new world we live in…Creativity can be unlimited so we started to tinker with an idea…When we decided to conceive of an idea, that was an idea that resonated with us.”

This project underscores the rising influence of NFTs in the art world. Last year, Michael Joseph Winkelmann, known as Beeple in the art scene sold his digital art, an NFT called “Everydays: the First 5000 Days,” for a whopping $69.3 million, making it the third most expensive artwork by a living artist to have been sold at an auction.

In March alone last year, a rising star of the Nigeria NFT space Jacon Osinachi sold NFTs worth $75,000.

What this project does is bring the conversation about returning arts that were looted in the colonial era to the NFT world. However, it is too early to quantify the impact that projects like this that draw on NFTs to create traditional, concrete, historical artefacts will have on the movement.

NFT sceptics could argue that making the Benin Bronzes ubiquitous could reduce their financial worth. The Benin Bronzes in the UK alone are estimated to be worth about £3.5 4.5 million. But that argument is dead on arrival because digital arts have existed with concrete art for years now and haven’t hampered the value of each other.

Like other tech innovative alternatives to traditional options, be it digital banks or bitcoin, they have coexisted complimenting each other, not seeking to annihilate the other and for years will do so.

The project hasn’t come to replace the Benin Bronzes, and frankly it can’t. What it can do is utilise the provisions of NFTs to increase the fight for the Benin Bronze to be returned back to its creators.

“We are here to accelerate awareness about the mask, about the rich culture in the West African Empire of Benin,” Anjorin said. “For years, they have been locked up and valued and shown to the public as ‘a library of the world,’ is what these museums call themselves. But these things were created here, on the ground, with methods so advanced.”

Copyright Laws

In December last year, the curator Ben Moore was sued for copyright infringement by the artist, Anish Kapoor after images of her life-sized Stormtrooper helmets was photographed by Moore and minted as NFTs.

At the start of this year, the NFT world was engulfed with debates over the PHAYC and PAYC (both meaning Phunky Ape Yacht Club) NFTs which both draw resemblance from the older and original Bored Ape Yacht Club (BAYC) NFTs.

And so the question remains about copyright laws. Is the Benin Bronze NFT Exchange Project in the clear in terms of copyright laws? For that Anjorin has an answer.

“If you’re using The Statue of Liberty on a face cap or T-shirt, it’s public domain property. So you don’t have to seek legal ramifications to do that. The Benin Bronze also falls into the same category. They’ve been in the public domain for so long.”

Is the Benin Bronze NFT Exchange Project sustainable?

The Benin Bronze NFT Exchange Project is already picking up steam on social media platforms like Discord, with rapper Lynxx joining the team as the spokesperson of the project.

But this is still a hard sell. Celebrities have always fancied themselves “serial entrepreneurs,” banking on their cache of social media followers loyal to their cause who will buy whatever merchandise they chose to hawk on the internet. But NFTs aren’t that type of merchandise. For one, they’re quite different from a concert t-shirt, face caps à la Vector or an edit collection in partnership with a fast-fashion company. NFTs like art can be very expensive.

The cost of minting a single NFT on the digital trading platform OpenSea can be anything from 70 to 200 dollars. All paid for out of pocket, the Benin Bronze NFT Exchange Project is printing 1897 of them. How would Anjorin and his team sell off 1,897 of them?

“We are trying to mitigate the gas fee not being astronomical for the local audience as much as possible,” Anjorin said. That way the prizes of the NFTs will be capped at a price point that is affordable for the average collector of NFTs.